If you want a quick, easy and condensed answer it would be because EON had to protect itself from what it felt were shady business practices that could potentially devalue the series; therefore a lawsuit was launched. And even after the new Bond film was given a start date to begin filming, it ended up having to be pushed back six months. The details of this tenuous, nearly seven year journey, would trace their roots back to studio unrest and lack of confidence extended towards License to Kill even before it had opened.

If you want a quick, easy and condensed answer it would be because EON had to protect itself from what it felt were shady business practices that could potentially devalue the series; therefore a lawsuit was launched. And even after the new Bond film was given a start date to begin filming, it ended up having to be pushed back six months. The details of this tenuous, nearly seven year journey, would trace their roots back to studio unrest and lack of confidence extended towards License to Kill even before it had opened.

1988-1989

MGM/UA began to have serious concerns about bankrolling Bond films in which they had little creative input. Albert Broccoli had bought United Artists 50% stake in Danjaq in the early 80`s (UA bought the shares in 1975 from Harry Saltzman when he sold his interest in the series and got out of the business of making Bond films) and thus retained 100% total creative control over the direction the series would take. But with the studio facing internal financial problems, they needed more bang for their buck, and were becoming less enthralled with Broccoli`s decision making.

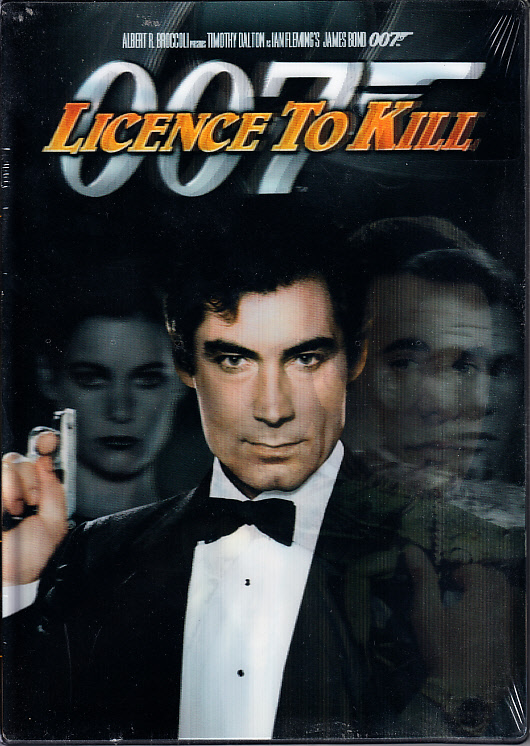

The tension began to manifest itself in the way in which MGM/UA marketed License To Kill, or should we say, didn`t market License To Kill. Bob Peak`s original artwork was scrapped in exchange for a low brow, lowest-common-denominator approach. His painted, “classic” style artwork was traded for a run-of-the-mill computer composite poster that featured Timothy Dalton, Robert Davi, Talisa Soto and Carey Lowell in a rather non-descript pose. The title was changed from the more poignant LICENSE REVOKED to the generic LICENSE TO KILL out of fear that the American audience was too stupid to differentiate a Bond film from a teenage driving flick. With the exception of a guest appearance on MTV by Talisa Soto, both she and Carey Lowell were conspicuously absent from print media, as well as television and radio talk shows to promote the film. It was enough to make Timothy Dalton, in 1989, declare to BONDAGE Magazine #16: “My feeling is this will be the last one. I don`t mean my last one. I mean the end of the whole lot. I don`t speak with any real authority, but it`s sort of a feeling I have. Sorry!”

Dalton probably knew more than he let on, but it was clear even to him that the series was already in danger and this was well before the messy legal action that would explode onto the scene one year later. Creative control issues were merely the beginning of Danjaq`s problems.

1989-1990

The North American box office receipts were abysmal: the film debuted in 4th place in its first weekend, dropped to 7th place in its second weekend and by the third weekend of release fell completely out of the Top 10. North American box office amounted to an underwhelming $34 million dollars (estimated). In August 1990 director John Glen and long time writer Richard Maibaum were unceremoniously dumped from the series. Variety Magazine quoted an anonymous, and apparently uninformed, EON insider as saying Maibaum was a “has-been” who had only contributed dialogue on the recent films.

The current script under development, which was to deal with robots run amok and take place in Scotland, Japan, and Hong Kong, was scrapped. At the same time, the August 8th issue of Variety reported that Cubby Broccoli put Danjaq, the company that holds the rights to the Fleming stories, up for sale and then handed over EON Productions to his daughter, Barbara Broccoli, and step-son Michael G. Wilson (to be fair, Michael and Barbara had been groomed for this responsibility for a long time and in conjunction with Cubby`s fragile health, this was as good a time as any to make a change). The asking price for Danjaq was a reported $200 million dollars, though conservative estimates placed the value nearer at $166 million. MGM/UA considered buying Danjaq, but balked at the steep price tag. Other big name players came and went on the financial scene, such as producer Joel Silver of “Lethal Weapon” fame. He was high on the idea of doing Bond and having his longtime friend and box office champ Mel Gibson play 007. But Silver, like others, found the exclusive distribution deal with MGM/UA too hard to swallow. No one wanted to be committed to a project that was tethered to a sinking studio.

The problems really began to pile up with the proposed merger of MGM/UA and Pathe Communications. Giancarlo Paretti, a corrupt Italian businessman with a long history of bank fraud and worthless checks, ran Pathe. Before Giancarlo even owned MGM/UA, he intended to sell off foreign television rights to the Bond series piecemeal in an effort to finance his takeover. He made outside deals with television networks in France, Spain, Italy, South Korea, and Japan without first consulting Danjaq. A deal with Ted Turner`s cable superstation TBS may have proven the most irksome. In his book “Bond and Beyond”, Tom Soter describes the prevailing attitude at the time towards the TBS deal for “James Bond Wednesdays”: “He (Cubby Broccoli) was angry about the way the previous movies had been sold to television–Ted Turner`s cable superstation TBS was running a Bond movie a week at one point-which Broccoli felt decreased the series value.” The TBS angle would become a side issue in a protracted two-year legal battle. Giancarlo Paretti bought MGM/Pathe on Oct. 22, 1990 for $1.3 billion and two days later signed a deal to sell 860 MGM/UA movie titles to Telecinco, a Spanish TV network. However, two weeks before that he signed a deal to sell 1,200 MGM/UA titles to Forta, another Spanish TV network.

Days before the merger though, Danjaq filed suit to block the deal. At the press junket for the movie GOLDENEYE, Goldeneye Magazine #4 (published by the Ian Fleming Foundation) recorded Michael Wilson`s comments in which he explained their strategic moves:”What happened was that Paretti took over MGM, and he wanted to have a leverage buyout, and we sued in federal court to enjoin him, and we failed, on the basis that if the leverage buyout went forward, that the company would be bankrupt, and four months later they were bankrupt.”

Kirk Kerkorian, who had sold MGM/UA to the Australian Company Qintex, sued over Paretti`s mismanagement. Kerkorian was in turn served with a shareholder lawsuit over his own sales of MGM/UA assets of back catalogue. In 1992, Crédit Lyonnais also brought a lawsuit against Kerkorian, claiming that Kerkorian had left MGM in financial disarray when he sold it to Paretti. Even Blake Edwards jumped in and sued MGM/Pathe over the rights to the Pink Panther series. Danjaq wasn`t the only company whose ties to MGM/Pathe seemed at times to be more of an albatross rather than a blessing.

1992-1993

After two years of litigation and negotiation Mr. Parretti lost control of MGM/Pathe to the French bank Crédit Lyonnais after defaulting on loan repayments in 1992. The French government in turn had to bail out Crédit Lyonnais to the tune of nearly $10 billion dollars. It had invested badly in the entertainment industry, and MGM/Pathe was just one of many bad judgement calls. Some Crédit Lyonnais bankers admitted they took bribes in exchange for overlooking Paretti`s questionable finances. Jean-Michel Raingeard, a spokesman for the Consortium de Realisation, the government company who liquidated Crédit Lyonnais assets, acknowledged: “This loss will be covered by the taxpayers at the end of the year”. Political heads rolled and a French Minister was sacked from his job. A consortium of buyers, led by Kirk Kerkorian, bought back MGM/UA. That deal left the French government, which took over MGM from the Crédit Lyonnais banking group, with roughly $1 billion dollars of losses.

Paretti had dropped out of sight for a while (thus prompting Crédit Lyonnais to declare him in default of his loan obligations) only to resurface in Italian court to answer to security fraud accusations. Paretti was wanted in both Europe and the United States.

In December of 1992 Pathe and Paretti were gone and MGM/Pathe went back to being MGM/UA. While the legal issues had dominated the Bond landscape for the better part of three years, it was now time to return to the issue of producing a new Bond film. By April of 1993 Michael France had been chose to write the new script.

1993-1995

Thinking the first draft would be turned in within twelve weeks, MGM/UA Chairman Alan Ladd proclaimed the project to be on the fast track. But that fast track had a few bumps along the way. France took longer to write the script than was originally expected. After rewrites by Bruce Feirstein, among others, it looked as if the project was all set. Filming was scheduled to begin August 1994 for a summer `95 release. Then, according to press reports at the time, TRUE LIES, Arnold Shwarzenegger`s 1994 film, came along and contained enough action sequence similarities to the current GOLDENEYE script that EON was forced to back off its August 1994 start date, rewrite the storyline and push production to January 1995. On January 16, 1995 principal photography began on GOLDENEYE in Leavesden, England. By the time GOLDENEYE was released in the United States on November 17th, 1995, nearly six and a half years had gone by.

Even if there had never been a single lawsuit filed and Paretti had never entered the picture, it is unlikely that another film would have been immediately made for release in 1991, nor would Dalton have returned to the role. The creative control issues became temporarily dwarfed by the litigation, but when the smoke and dust cleared from all of that, Dalton found himself right back where he started: on the hot seat. John Calley, CEO of MGM/UA in 1994 and 1995, was reportedly adamant that a new Bond be hired for the next film. Dalton was the “Bond of record”, but gracefully bowed out of the role, thus saving Albert Broccoli from having to make the hard call of firing Dalton.