MORRIS CARGILL, who has died in Jamaica aged 85, was for almost half a century the best-known journalist in the Caribbean; his column in Jamaica`s national newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, was regarded by many as the only accurate account of the state of affairs of the country, and was required reading for politicians and plumbers alike.

MORRIS CARGILL, who has died in Jamaica aged 85, was for almost half a century the best-known journalist in the Caribbean; his column in Jamaica`s national newspaper, The Daily Gleaner, was regarded by many as the only accurate account of the state of affairs of the country, and was required reading for politicians and plumbers alike.

Although Cargill delighted above all in pricking pomposity, he did not hold back from giving his own authoritative view. “I know it`s very trendy to admire reggae,” he wrote. “Well, I don`t. I am stubbornly of the opinion that it is fit only for semi-literate tone- deaf morons . . . I wouldn`t dream of using an amplifier to bash people in the street with Beethoven.”

Taken with his other much-aired dislikes – tough steaks, computers, bad English – such attitudes might be thought to be those of a world-weary reactionary. Instead, Cargill was in favour of decriminalising marijuana, loathed racists, had converted to Buddhism and distrusted authority.

“Jamaica and its politicians,” he believed, “are West Indian ramshackle, Mrs Malaprop, Black Mischief and the Mafia all tied up in one parcel.”

Provocative commentary like this divided even the many who admired his writing and brought charges that he was unpatriotic, which he was not. Instead, together with respect for the family, nothing was dearer to him than Jamaica`s future, which he despaired would be destroyed by nationalism. He made it his task to confront any such threat with humour, and fearlessness.

Morris Cargill was born in the parish of St Andrew, Jamaica, on June 10 1914. His ancestors were Scottish Covenanters who had settled in Jamaica in 1666 and over the centuries acquired large plantations. His father was a a partner in the law firm of Cargill, Cargill and Dunn.

Young Morris grew up in Kingston, where his Jamaican nanny kept colds at bay by liberally dosing him with marijuana. He was sent to school locally at Munro College, although in practice he spent much of his time on his uncles` plantations, and then at 13 was dispatched to Stowe, in Buckinghamshire. From there he would return home only for the summer holidays, making the journey by banana boat.

Cargill decided to follow his father into the law, and in 1937 was admitted a solicitor in Jamaica. But he soon decided this was not for him, and became instead the manager of the Carib Theatre, a cinema in Kingston.

In 1941, he and his wife Barbara sailed for England to make their contribution to the war effort. Cargill worked first for the Ministry of Information and then as business manager of the Crown Film Unit. He also broadcast occasionally on the BBC.

After the war, he went into business for himself, importing Jamaican rum and a coffee-based liqueur he had had made up to his Aunt Mary`s recipe. This latter venture was not at first a success, and so Cargill sold his rights to Tia Maria. He fared better with his interests in steel and plastics.

Cargill returned home in 1949 and once more changed career, buying a 720-acre banana plantation, Charlottenburgh, in St Mary. He gradually modernised the cabins of his plantation workers, and valiantly tried to introduce birth control.

He gave hundreds of sponges to young women for use as simple barrier contraception, but then discovered that they were using them instead to wipe clean their slates in school. The local population continued to grow apace.

Farming in Jamaica, said Cargill, was a mixture of running an institution for delinquents and being both medical orderly and magistrate. His labourers trusted him to settle all their disputes rather than go to court.

He kept up his interest in journalism and broadcasting and in 1952 began to write a daily column in the Gleaner under the name “Sam White”. Soon his opinions were being read all over the West Indies. Then in 1958 he was, somewhat against his better judgment, elected to the short-lived Parliament of the West Indies Federation as the member for St Mary.

This meant moving to Trinidad, where, while serving as Deputy Leader of the Opposition, he also edited the Port of Spain Gazette. He felt under-employed, however, and in 1963 resigned to return to Jamaica, where he resumed both farming and writing his column.

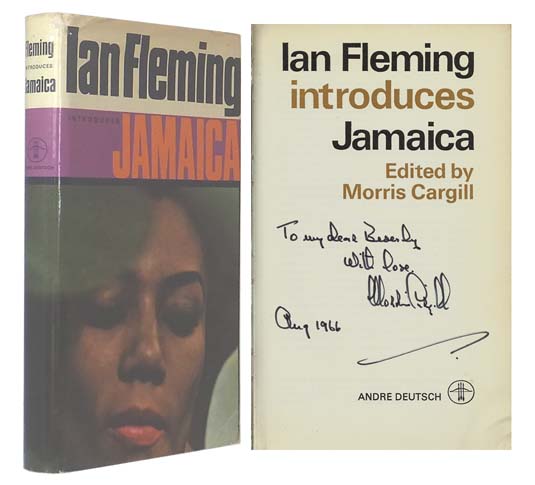

His friends and neighbours in St Mary included Noel Coward and Ian Fleming, who had James Bond seek information about Jamaica from Cargill in two of his books, Dr No and Octopussy. But by the 1970s, danger had began to enter Cargill`s life off the page. He was badly wounded by a man attempting to rob his house and then, with the advent of Michael Manley`s socialist government, was three times threatened with prosecution for criticising the Prime Minister in his column.

A campaign to drive Cargill out of Jamaica now began. The last straw came when the water to his plantation was cut off and he was forced to sell Charlottenburgh. He took a publishing job in Connecticut and, allowed to take only $50 with him, moved to America. There he wrote a memoir, Jamaica Farewell (1977).

A change of government, however, brought him back, and with his half-brother John Pringle, now Jamaica`s Ambassador-at-large, he bought a large estate near Hope Bay, Portland, called “Paradise Plum”. But the plantation was devastated by a hurricane and floods, and in 1982 he gave up farming and moved to Kingston to concentrate on journalism.

Although ill health and near-blindness had latterly confined him to a wheelchair, he still wrote his column three times a week until just before his death.

Cargill was, despite the strength of his opinions, a kind and considerate man. His books included A Gallery of Nazis (1977) and three thrillers written with John Hearne under the pseudonym John Morris. A Selection of Writings in the Gleaner, 1952-85 appeared in 1987, and was followed in 1998 by another collection, Public Disturbances.

Morris Cargill was appointed a Commander of the Order of Distinction (Jamaica) for services to journalism in 1998. He described it as a “sort of equivalent to the CBE, and only given to extinct volcanoes”.

He married first, in 1937, Barbara Margot Samuel. They were divorced in 1972, but remained on friendly terms and took their holidays together. They adopted a daughter, who survives them both. A second marriage was also dissolved.