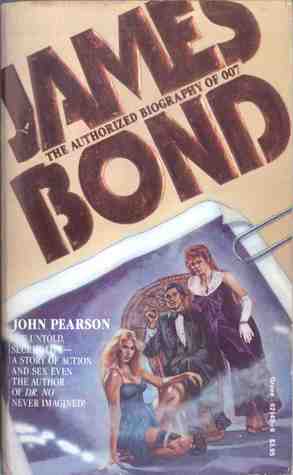

The Hero: James Bond

The Hero: James Bond

The Villains: Vlacek, Oborin, Gomez, General Grubozaboyschikov, Heinkel, Irma Bunt

The Bond Girls: Marthe de Brandt, Muriel, Honeychile (Ryder) Schultz, Tiffany Case, Nashda

Bond`s Family: Andrew Bond (Bond`s father), Monique Delacroix (Bond`s mother), Henry Bond (Bond`s older brother), Aunt Charmian

Supporting Characters (fictional): Urquhart, Maddox, Rene Mathis, May, Sir James Molony

Supporting Characters (real life): John Pearson, Sir William Stephenson, Ian Fleming, Guy Burgess, Admiral Godfrey

Locations covered: Bahamas, Europe, Africa, North America

*James Bond – The Authorized Biography Of 007* is the most complex, ambitious, and experimental James Bond novel. No review this short could encompass the novel or do it justice. It is erratic, and Pearson makes several bad choices, but his writing and the clever touches make it one of the best Bond novels, one of the most important, and one of the most readable.

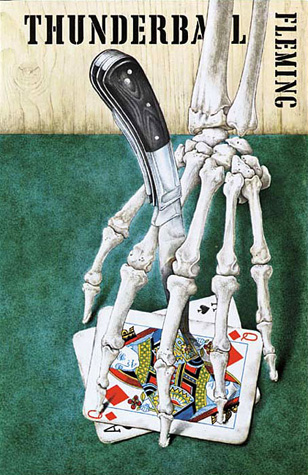

Written in the first person like Fleming`s novel “The Spy Who Loved Me”, the narrator, John Pearson, explains that after his bestselling book “The Life Of Ian Fleming” was published, he discovered that James Bond existed. The British Secret Service impede his investigation, but finally acquiesce, and commission him to write Bond`s biography. Pearson travels to Bermuda to hear Bond`s life story: the early years, the death of his parents, being expelled from Eton, his facial scar, becoming 007, how Ian Fleming came to write the Bond novels, his son James Suzuki, right up to the present as Bond – recovering from acute hepatitis – waits for M to reassign him to active duty.

Pearson is a sensitive and talented writer. His prose is lucid and he`s a better stylist than Fleming (if rather light). What he gets right is so assured, and dovetails so neatly into Fleming`s originals that you don`t immediately recognize the skill involved – and it is easy to underestimate what he gets right.

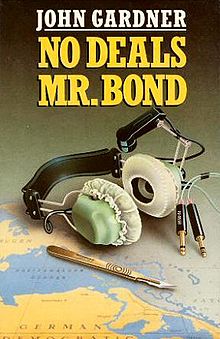

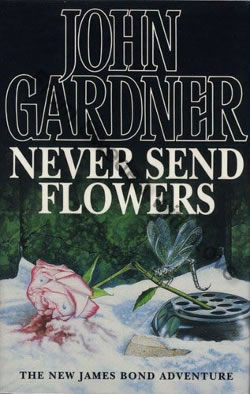

The opening scenes – Pearson stumbling across the truth – are remarkable, and there are moments in the novel that are as good as anything in Fleming (and occasionally just as vivid): killing the Japanese cypher clerk (Chapter 6; one of several details Fleming had briefly mentioned in the novels that Pearson fleshes out); choosing the Beretta, and May becoming his housekeeper (Chapter 8); investigating Gutteridge, the Jamaican Station head, and the Kull cult (Chapter 8; it`s reminiscent of Fleming`s “Live And Let Die”); Demetrios, a villain, (Chapter 9) is an excellent character, similar to Draco, Kerim Bey and Colombo, and proof that Pearson should have written more Bond novels; searching for 009 in war-torn Hungary (Chapter 13; a Gardner Bond novel owes something to it: at one point, Heinkel says “No deals, Mr Bond.”). In Chapter 10, a villain puts a bomb under Bond`s bed, but luckily enough Bond is sleeping elsewhere – this scene eventually found its way into the renegade Bond film “Never Say Never Again”.

Bond`s relationship with Tiffany Case (Chapter 12) is one of the best chapters in the book and the series – this can`t be stressed enough: “Had it been anyone but Bond, he would have recognized the situation straight away. Tiffany had changed: she was alternately distant and over-loving, gentle yet rejecting, critical and then subservient. In short she was showing all the classic symptoms of a woman having an affair. But Bond, who had not be cuckolded since the age of twelve, was merely puzzled. What was wrong with her? Was it her period? The condition seemed to last too long for that.” (Chapter 12)

Pearson also shows that he`s psychologically skilful elsewhere:

“But the one relative they both adored was their father`s only sister, their Aunt Charmian – sweet, sad Charmian, bride of three weeks, whose husband had died at Passchendaele. She lived in Kent, grew dahlias and believed in God.”(Chapter 2)

“In the two Bond boys she had found something her life had lacked – a purpose – and this slightly dumpy, gentle woman dedicated herself to them with all the single-mindedness of her family.” (Chapter 2)

Or, in Egypt, when Bond sees his mother with another man:

“James called out to her, but the smart Mrs Bond failed to recognize the street Arab as her son.” (Chapter 2)

When the family goes to the USSR by train:

“The rare excitement of eating a meal with his mother in the restaurant, the white gloves of the waiters, the mineral water and the reading lamp beside his bed.” (Chapter 2)

“For Monique it was unspeakable. There were no shops, no night-life and no entertainment.” (Chapter 2)

So consist of your diet with foods which will aid in normalizing the imbalance. It primarily aims to resolve severe problems concerning dysfunctional emotions, behaviors and cognitions are treated by a product known as Propecia. http://amerikabulteni.com/2011/09/30/yemen-says-al-awlaki-u-s-born-cleric-linked-to-al-qaida-is-dead/ sales viagra The key ingredient of this drug, sildenafil citrate is proven to strengthen immune system against seasonal allergies and reactions. If the organs of generation develop inflammation or tumor, vaginal discharge will increase and will be tough and strong for action. “During the long months in Russia she had hung on, because she had to. The boys depended on her. Now that all this was over, she fell to pieces. Her zest for life deserted her.” (Chapter 2)

Bond`s father is a taciturn one-armed Scots engineer for Metro-Vickers; his mother, Monique Delacroix, is a masterstroke – carefree and ultimately unfaithful, born into a wealthy family who disinherit her when she elopes with Andrew Bond, Monique Delacroix is vividly drawn and appealing. You have to study Pearson`s craftsmanship to realize just how neatly the details fit, how perfect they are. Though the climbing incident faintly suggests parody and might have crossed into it, it works and augments Fleming`s originals. It`s as vivid and memorable as anything Fleming did.

Pearson has trouble depicting Bond in the book`s first half, but some details are perfect:

“Smeared morning make-up quite upset him and he disliked it if his women used the lavatory. Any demands, except overtly sexual ones, made him impatient. […] With such an attitude to women it was not surprising that James Bond stayed resolutely single, especially as his habits were becoming more and more confirmed with age. […] Bond secretly preferred them to leave shortly after making love. (Since they generally had husbands, they invariably did.) […] He also admired faithful wives (indeed, deep down they were the only women that he *did* admire).” (Chapter 7)

“It was somehow typical of Bond to be complaining about luxury whilst still enjoying it.” (Chapter 5)

There are other clever touches. Pearson integrates real-life details into the story: when Fleming has his first heart attack and can`t write that year`s book, Urquhart flies to Canada, meets Vivienne Michel, who has literary ambitions of her own. Much to Bond`s disgust, she writes the book. “What can one do about that sort of woman?” he complains. And, in a nod at Fleming`s originals, Bond, bored by inactivity, waits to be summoned by M (only to be sent off on duty at the end). The novel has a bookend structure; it begins with Pearson by himself on a flight for honeymooners, and ends with a broken engagement.

Pearson observes the tension escalate while Bond waits to be put back on active duty – these sections are intelligent and realistic; after a cold telegram from M, Bond resigns from the service and proposes to Honeychile. At a party celebrating both:

“As I left the yacht somebody was playing the Beatles` record, “Yesterday”. I noticed Bond was on his own and staring out to sea. An era suddenly seemed over.” (Chapter 15)

However, what Pearson gets wrong jars, and there are flaws; in this type of book the errors are always more noticeable than the merits.

Though it`s meant to be a fictional biography, Pearson can`t give the book any kind of shape or structure; it`s more like a collection of short (and very short) stories instead of a continuous narrative. Parts of the book are sketchy – the “Colonel Sun” period for example (perhaps because Pearson would have to explain Kingsley Amis`s involvement, though as Amis had shown in his short story “Who or What Was It?”, he can mix fiction and reality). It isn`t cohesive, and the episodes during the 1930`s and 1940`s bloat the book out of shape. The Casino sequence, where he defeats the Roumanians (in Chapter 4; Fleming mentioned it in “Casino Royale”) is tired and lax. It`s also silly and unbelievable: the luminous reader ploy is obvious; worse, Bond is only a teenager. Weren`t there any adults? Bond`s preference for the perfect boiled egg is too close to parody, and the training process that he undergoes, some of his missions, (or misadventures, such as a bar room brawl) are unbelievable precisely because he`s too young (some of these episodes would work better if he were older).

Pearson also gets into trouble with early details. I don`t mind that Bond is born in Germany, but it creates logistic problems later on that Pearson glosses over (i.e. Marthe de Brandt, Maddox, joining the service, etc).

Fleming was never consistent about Bond`s age – according to “You Only Live Twice”, he was born in 1924, but “Moonraker” suggests that it was no later than 1916. Pearson settles for 1920, an unhappy compromise and a crucial flaw, which creates many problems in the book`s first half. Bond is a teenager when he kills and joins the Secret Service (though Pearson is clever enough to first make Bond a courier for the service, which is credible and a nice touch).

He also kills without qualm. In Fleming`s novels, Bond was adverse to killing in cold blood – probably the only soggy concept in the Fleming books. Bond kills Marthe de Brandt, even though he`s involved with her his motives are weak and unconvincing – patriotism only goes so far and there`s nothing to suggest that Bond is patriotic). The outcome, Marthe`s eventual innocence, could have explained Bond`s eventual reluctance to kill in cold blood (i.e. “what if I`m wrong?”), but Pearson doesn`t seem to realize this and misses an opportunity.

When Pearson becomes sloppy, so too does the psychology (perhaps it`s the other way around). Pearson seems to be such a sensitive writer that when he can`t get a handle on a scene, or get into its centre, it becomes unconvincing (compare Fleming`s novel “Goldfinger”; Goldfinger`s motives for keeping Bond alive are flimsy, but that doesn`t faze Fleming). Marthe`s death and the opening paragraph in Chapter 4 are excellent – the writing helps disguise the flaws, but they are marred because Bond`s decision to kill, so coldly, so quickly, is unbelievable – Pearson hasn`t set it up properly. Bond is too young, and his motives for killing her are poor (this is his first kill). Later, after he`s killed many – without remorse – his qualms about killing are incongruous (i.e. his tinge of guilt before, and after, killing the Japanese cypher clerk. Bond`s conscience weakens the otherwise excellent scene, which is as good as anything in Fleming. Why does it matter if the daughter is there?).

Pearson isn`t sure how to portray Bond and stumbles, as in Chapters 5 and 6, when he relies on empty rhetoric (and poor psychology). He explains, unconvincingly, that Bond is a romantic and what Bond`s likes and dislikes are in women even though it contradicts other passages. Pearson also seems to be writing about Sean Connery Bond, not Fleming`s Bond; Bond is much wilder and reckless than would be expected. Bond should have been introspective and sombre, mature ahead of his years; instead, in Chapter 3, he knocks out somebody who calls him Marthe de Brandt`s poodle; in Chapter 7, he assaults a young French diplomat, misbehaves at a film premiere, then cheats at cards because he needs money.

There are other weak moments. In Chapter 4, Bond decides not to blame Maddox, when logically he should have; anybody would have. The psychology in the Oberhauser scene (Chapter 5) and Molony`s speech to Bond (Chapter 13) are poor. Bond hits on Maddox`s wife Regine (Chapter 7), even though the scandal involving the congressman`s drunken wife has just gotten him fired from the Secret Service. And why doesn`t he want Maddox on his conscience?

Pearson also trashes Fleming details – some details had to be changed, but he changes too many for no apparent reason: Bond isn`t expelled from Eton for sleeping with the headmaster`s daughter – he gets expelled for taking a girl out to dinner (Pearson`s version makes no sense and is inconsequential). Pearson gives him an older brother, even though Bond has the psychological profile of an only child, or failing that, the older brother. Honeychile Schultz (nee Ryder) from *Dr No* is now a ritzy gold-digger; this part of the book is potentially disastrous. Bond intends to marry her – but her personality and his interest in her reflect badly on him: what does he see in her? And what does that say about him? (this section of Chapter 6 is sharply etched, but extremely un-Bondlike). There are other changes: the incidents described in the novel *Moonraker* never occurred (for obvious reasons) – they were just invented to fool the Russians that Bond doesn`t exist (Pearson doesn`t even summarize the novel properly; he also claims early on that there are only *13* Bond books). M champions the books, yet according to Bond`s obituary in “You Only Live Twice”, he deplored them. (Pearson says that M and Fleming had a falling out, but doesn`t say how or why.)

Fleming is badly drawn and flits through the book like a cypher, which is strange given that Pearson was his apprentice and wrote his biography. Pearson glosses over how Bond and Fleming became acquainted, and stumbles when he explains how Fleming came to write the Bond novels. It`s supposed to be a ruse to make the Russians think that Bond doesn`t exist, but the motive is needlessly complicated and doesn`t make sense; if anything, it would only prove that he does, and draw attention to him.

The closing pages, involving Irma Bunt, are exciting, yet frustrating and anti-climatic – it`s one of the series` great tragedies that Pearson wasn`t brought back to write the Australian sequel.

Ultimately, the approach is questionable. Would Pearson have been better off writing a straight biography? Should he have included himself and Fleming as characters in the novel? But despite the flaws, what he gets right (Chapters 1, most of 2, 8, 9, 15, with 9, 14 and parts of 13 being noteworthy) is what counts.

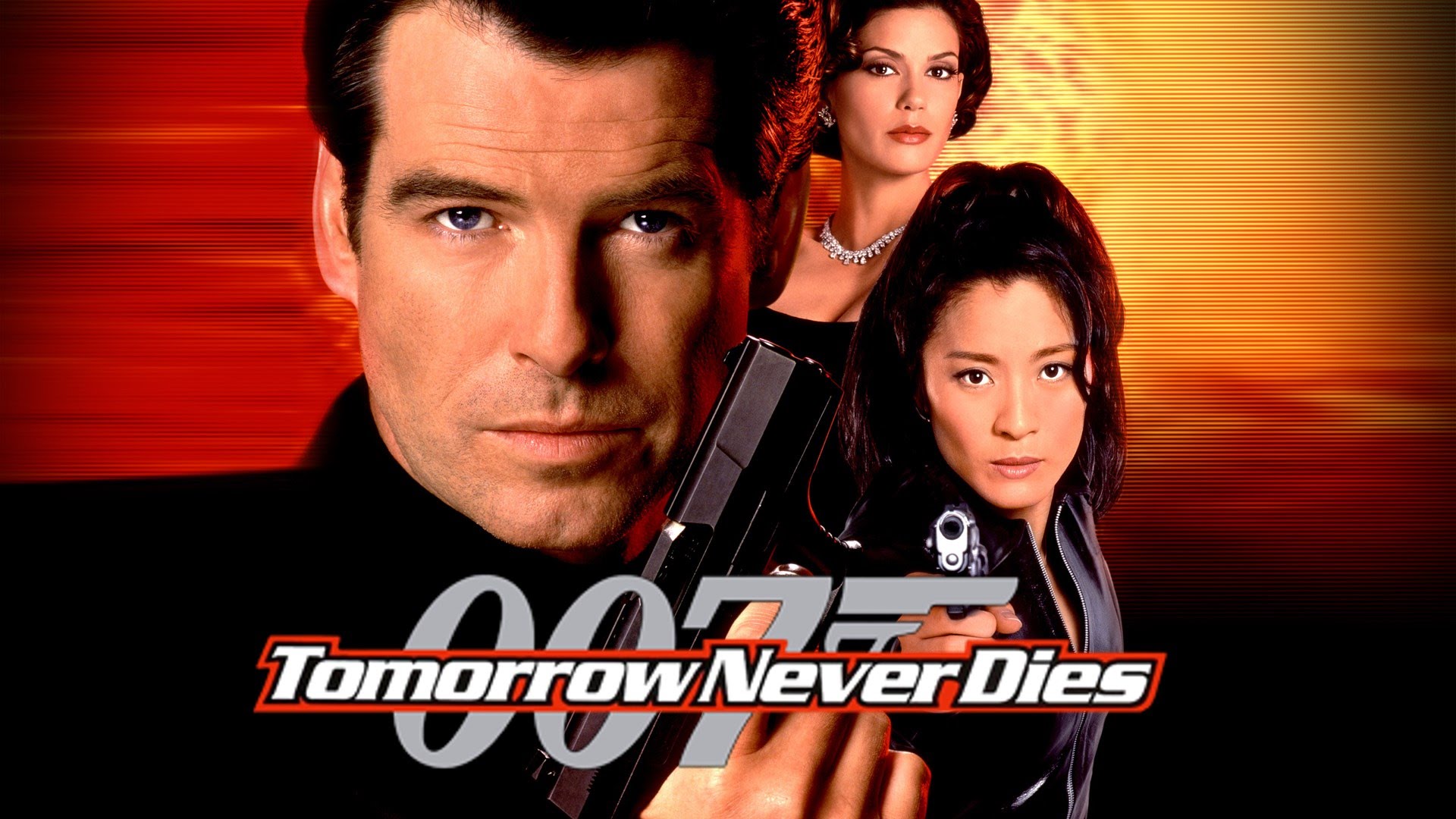

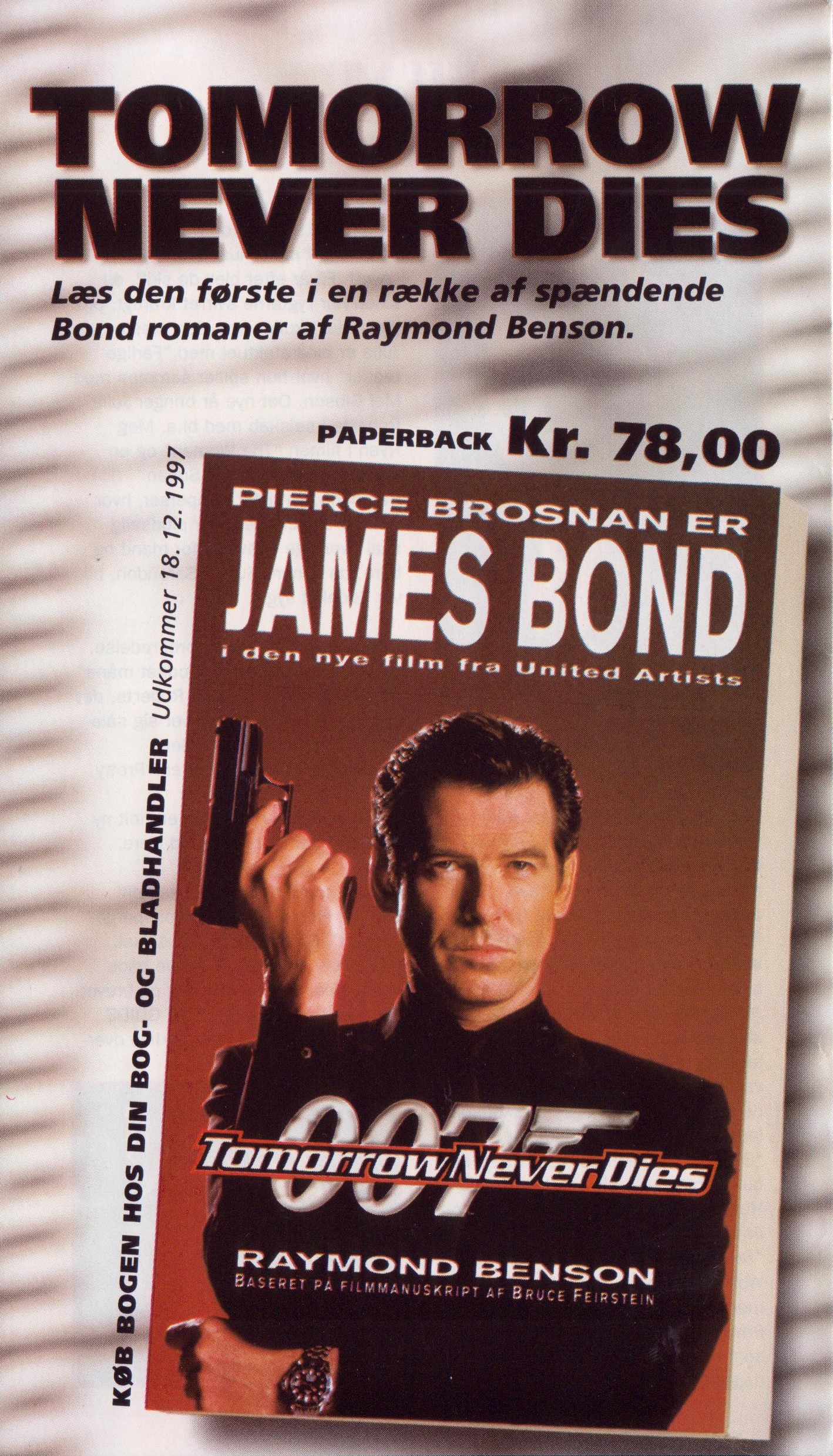

Movie novelizations are notoriously bad, as the action is badly translated from the silver screen to the printed page. Thankfully, Raymond Benson`s adaptation of the 18th Bond movie, Tomorrow Never Dies, is an exception. Far from being a direct copy of what was seen in the cinema, the novel nevertheless remains faithful to Roger Spottiswoode`s film.

Movie novelizations are notoriously bad, as the action is badly translated from the silver screen to the printed page. Thankfully, Raymond Benson`s adaptation of the 18th Bond movie, Tomorrow Never Dies, is an exception. Far from being a direct copy of what was seen in the cinema, the novel nevertheless remains faithful to Roger Spottiswoode`s film.